Replacement dental implants: 3 clinical methods to increase survival rates after initial implant failure

Editor's note: Originally published June 5, 2018. Formatting updated January 2023.

Dental implants have traditionally enjoyed high survival rates as reported in the literature.1 Complications can occur, however, and dental implant failure and removal have been reported to be in the average range of 5% to 12%.2 After an implant is removed, the patient is left with a difficult decision regarding replacement options.3 A removable prosthesis may be a possibility, but it is often not the first choice of therapy. A fixed partial denture on adjacent natural teeth can also be a treatment option if there is a single implant site failure. This option is predicated, however, upon the patient agreeing to preparation of the natural teeth as well as the abutment teeth having enough periodontal support to withstand the forces of a bridge. Most of the time, the patient will choose to replace the failed dental implant with placement of another implant.

Replacement of a failed dental implant with a second implant has varying survival rates in the literature, and have been reported to be in the range of 69% to 91%.4,5 In addition to having lower success rates than the initial implants, replacement implants often require additional soft- and/or hard-tissue grafts, longer time to heal, new abutments/crowns, and possible additional financial costs for the patient. Prior to reimplantation, ascertaining the etiology of the initial implant failure is certainly warranted. In addition, methods to improve osseointegration of the replacement implant should be employed.

Here are three clinical tips to improve the dental implant survival rate after initial implant failure ...

Thorough removal of fibrous soft tissue from the dental implant socket

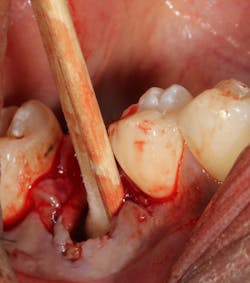

An implant that has lost integration can suffer from fibrous downgrowth (encapsulation) of the entire implant body (figure 1). This tissue acts a barrier to bone-to-implant contact and osseointegration of the replacement implant.6 It is imperative to thoroughly debride the implant socket and meticulously remove all soft tissue prior to implant placement. Proper instrumentation will allow the clinician to reach the apex of the implant socket and be sharp enough to perform curettage on the osseous walls of the socket (figure 2). After complete tissue removal, chemical modification is the next step.

Figure 1: Radiograph showing complete loss of integration and fibrous encapsulation

Figure 2: Slade Blade socket curette (Paradise Dental Technologies) being used to remove fibrous soft tissue from the residual implant socket

Complete debridement of bacteria in the implant socket and surrounding tissue

Failing implants that are afflicted with peri-implantitis usually are exposed to the same pathogens that affect natural teeth.7 These bacteria not only can coat an implant surface, but they also can be found in the surrounding peri-implant tissue. Complete removal of these bacteria via chemical detoxification of the residual implant socket and surrounding tissue can assist with removal of the pathogens (figure 3). Although both are effective, chemical modification with a neutral EDTA with a pH of 7.4 is a kinder alternative to tissue compared to 60% citric acid with a pH of 1. In addition, laser sterilization of the inflamed soft tissue surrounding the failed implant can help increase tissue tone during healing (figure 4).

Figure 3: Cotton pellets soaked with 60% citric acid used to detoxify an implant socket

Figure 4: Laser sterilization of soft-tissue flap during implant removal to facilitate healing

Increase angiogenesis to the hard and soft tissue

Vascularity to the hard and soft tissue surrounding a dental implant is vital to its osseointegration. Because the implant surface itself is avascular, blood supply to the area is a challenge. When an implant fails, the vascularity of the surrounding tissue can be further damaged. Any enhancement to the angiogenic potential of the hard and soft tissue can only help a second attempt at implant placement. Decortication of the implant socket with a precision needle drill or round carbide has been suggested to increase blood supply to the area. The addition of exogenous growth factors and proteins—such as platelet-derived growth factor, leukocyte platelet-rich fibrin, enamel matrix derivative, and bone morphogenic proteins—have all been used to enhance the angiogenic response.

Although implant replacement after an initial failure has been shown to have a lower success rate compared with initial implant placement, the three methods discussed in this article can increase survival rates of reimplanted dental implants. Ultimately, an informed and honest discussion regarding the challenges of implant replacement should occur between the patient and the clinician before beginning any treatment.

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in Perio-Implant Advisory, a chairside resource for dentists and hygienists that focuses on periodontal- and implant-related issues. Read more articles and subscribe to the newsletter.

References

- Levin L, Sadet P, Grossmann Y. A retrospective evaluation of 1,387 single-tooth implants: a 6-year follow-up. J Periodontol. 2006;77(12):2080-2083. doi:10.1902/jop.2006.060220

- Esposito M, Grusovin MG, Coulthard P, Thomsen P, Worthington HV. A 5-year follow-up comparative analysis of the efficacy of various osseointegrated dental implant systems: a systematic review of randomized controlled clinical trials. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2005;20(4):557-568.

- Levin L. Dealing with implant failures. J Appl Oral Sci. 2008;16(3):171-175. doi:10.1590/S1678-77572008000300002

- Duyck J, Naert I. Failure of oral implants: aetiology, symptoms and influencing factors. Clin Oral Investig. 1998;2(3):102-114.

- Grossmann Y, Levin L. Success and survival of single dental implants placed in sites of previously failed implants. J Periodontol. 2007;78(9):1670-1674. doi:10.1902/jop.2007.060516

- Zhou W, Wang F, Monje A, Elnayef B, Huang W, Wu Y. Feasibility of dental implant replacement in failed sites: a systematic review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2016;31(3):535-545. doi:10.11607/jomi.4312

- Quirynen M, Listgarten MA. Distribution of bacterial morphotypes around natural teeth and titanium implants ad modum Brånemark. Clin Oral Implant Res. 1990;1(1):8-12.

About the Author

Scott Froum, DDS

Editorial Director

Scott Froum, DDS, a graduate of the State University of New York, Stony Brook School of Dental Medicine, is a periodontist in private practice at 1110 2nd Avenue, Suite 305, New York City, New York. He is the editorial director of Perio-Implant Advisory and serves on the editorial advisory board of Dental Economics. Dr. Froum, a diplomate of both the American Academy of Periodontology and the American Academy of Osseointegration, is a volunteer professor in the postgraduate periodontal program at SUNY Stony Brook School of Dental Medicine. He is a PhD candidate in the field of functional and integrative nutrition. Contact him through his website at drscottfroum.com or (212) 751-8530.