Bad breath caused by leaky gut: Nutrition may help both problems

Leaky gut is a condition where toxins, bacteria, and/or undigested food particles leak through a damaged part of the digestive track and enter the bloodstream, initiating an immune response that can interact with different systems of the body. Leaky gut, which results from intestinal permeability, can exacerbate irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), irritable bowel disease (IBD), and celiac disease (CD), which are common gastrointestinal disorders that affect around 10%–15% of the US population.1

Leaky gut can be associated with halitosis (bad breath) since many of the pathogenic bacteria that release volatile sulfur compounds and cause bad breath also play a part in the development of intestinal permeability. Leaky gut is multifactorial, with nutrition being one of the more important etiologies. This article will focus on how proper nutrition can mitigate leaky gut and in doing so, potentially help with bad breath.

How do I know if I have leaky gut?

25%–88% of people who have leaky gut can experience these typical symptoms:

- Halitosis and/or a change in breath

- Gastrointestinal issues such as abdominal pain, cramping, bloating, and alternating diarrhea or constipation

- Changes in stool composition, frequency, and a feeling of incomplete bowel movements

- Less obvious correlations include depression, anxiety, insomnia, skin conditions, joint pain, and high environmental reactivity.

What causes leaky gut?2

Although there are many reasons why the gut lining (small intestinal lining) can become inflamed and the tight junctions of this lining become permeable, the following reasons are the top causes3:

- Diet including ultra-processed food, excessive alcohol intake, foods containing high pesticide concentrations, and high fermentable oligo di mono and polyol (FODMAP) foods

- Food intolerance/sensitivities, most notably dairy (lactose), gluten (gliadin), soy, eggs, wheat, nuts (peanuts and almonds), and corn

- Stress

- Infections and autoimmune diseases

- Medications such as antacids and antibiotics

How do I check for a leaky gut?

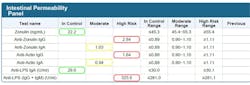

If you are experiencing the symptoms of a leaky gut, the gold standard for testing is:

Best nutrition practices to improve leaky gut and bad breath

Although it is known that foods such as garlic and onion can cause bad breath, this problem is transient and usually goes away. Unfortunately, for people with leaky gut, these foods can be particularly damaging as they exacerbate both intestinal permeability (high FODMAP) and bad breath. FODMAP foods are foods that are easily fermented by gut bacteria that can cause inflammation and volatile sulfur compounds. The following nutritional pathways are the best ways to fix leaky gut and improve bad breath due to leaky gut:

- Probiotics4: One of the most effective methods of promoting healthy bacteria and lowering inflammation is through the use of probiotics that use a combination of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species 1–10 billion CFU for two to three months (figure 3). StellaLife Oral lozenge probiotic and gut spore biotic is an excellent combination of these eubacteria that can improve halitosis caused by leaky gut (figure 4).

- Whole foods, not ultra-processed foods: Ultra-processed foods typically have additives such as emulsifiers, dyes, and chemicals that preserve shelf life but can damage the stomach lining and cause inflammation.

- Low FODMAP diet5: This may be particularly challenging as “healthy foods” can be high FODMAP, so people with leaky gut should avoid foods such as garlic, onions, asparagus, avocado, apples, watermelon, etc. (figure 5).

- Fermented foods: Foods such as kefir, live sauerkraut, low-sugar kombucha, tempeh, miso, and kimchi promote healthy bacteria that decrease inflammation.

- High polyphenol diet: The antioxidant properties of berries, foods high in omega-3, dark chocolate, spinach, and flaxseeds can lower inflammation.

- Prebiotics: Prebiotics including fiber (psyllium husk is a great choice)

- Spices: Peppermint, clove, and turmeric act as anti-inflammatories.

- Moderation of alcohol6: Two or three drinks per week do not have a deleterious effect on intestinal permeability. More than this amount can be damaging to the intestinal lining.

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in Perio-Implant Advisory, a chairside resource for dentists and hygienists that focuses on periodontal- and implant-related issues. Read more articles and subscribe to the newsletter.

References

- Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). American College of Gastroenterology. https://gi.org/topics/irritable-bowel-syndrome/

- Chelakkot C, Ghim J, Ryu SH. Mechanisms regulating intestinal barrier integrity and its pathological implications. Exp Mol Med. 2018;50(8):1-9. doi:10.1038/s12276-018-0126-x

- Camilleri M. Leaky gut: mechanisms, measurement and clinical implications in humans. Gut. 2019;68(8):1516-1526. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318427

- Zheng Y, Zhang Z, Tang P, et al. Probiotics fortify intestinal barrier function: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1143548. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1143548

- Camilleri M, Vella A. What to do about the leaky gut. Gut. 2022;71(2):424-435. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2021-325428

- Bishehsari F, Magno E, Swanson G, et al. Alcohol and gut-derived inflammation. Alcohol Res. 2017;38(2):163-171.

About the Author

Scott Froum, DDS

Editorial Director

Scott Froum, DDS, a graduate of the State University of New York, Stony Brook School of Dental Medicine, is a periodontist in private practice at 1110 2nd Avenue, Suite 305, New York City, New York. He is the editorial director of Perio-Implant Advisory and serves on the editorial advisory board of Dental Economics. Dr. Froum, a diplomate of both the American Academy of Periodontology and the American Academy of Osseointegration, is in the fellowship program at the American Academy of Anti-aging Medicine, and is a volunteer professor in the postgraduate periodontal program at SUNY Stony Brook School of Dental Medicine. He is a trained naturopath and is the scientific director of Meraki Integrative Functional Wellness Center. Contact him through his website at drscottfroum.com or (212) 751-8530.

Nathan Estrin, DMD

Nathan Estrin, DMD, received his bachelor’s degree in kinesiology from Indiana University and went on to earn his DMD from LECOM School of Dental Medicine. He received his training in periodontics at Stony Brook University in New York. During his dental studies, he developed a passion for regenerative, implant, and laser surgery and has more than 15 publications and three book chapters in these areas. Dr. Estrin is a board-certified periodontist in full-time private practice in Sarasota, Florida. He is also adjunctive faculty at LECOM School of Dental Medicine and a lead educator for PRFedu, where he trains dental offices on platelet-rich fibrin, lasers, and modern periodontal therapy.