Teeth have multiple purposes. Aside from biting and chewing food, they improve quality of life, particularly as they play an important role in speaking and smiling.1 When disease occurs, a common prognosis by clinicians is to remove the offending teeth and replace them with implants. With most other organs in the body, preservation is the goal. However, teeth are more likely to be extracted without consideration of alternative methods to retain them, when, in fact, multiple options are available for preventing disease and saving teeth.

Reports concur that despite the ability to save teeth through improved periodontal therapy and evidence supporting the fact that maintenance is preferable to replacement, there has still been an increase in extractions and a coinciding proliferation in the use of implants.2

When is intervention needed?

Many reasons provoke the need for tooth extraction. In younger people, common causes are caries and trauma; older clients often suffer from periodontal disease or fractured roots due to trauma or parafunctional habits.3 Dental professionals understand the potential impact on an individual’s oral health from toxic biofilm.4 The bacteria living in the crevicular fluid induces inflammation that can lead to periodontal disease or create cavitations in the teeth. When the biofilm becomes dysbiotic and toxic, this can lead to loss of teeth. If patients are unable to manage their biofilm at home, it can cause problems for future implants too.

Dental implants may be a solution, but why should we preserve teeth first?

When comparing an implant with other options, it is essential to acknowledge all possible outcomes. Often, immediate postimplementation success is taken into consideration, but it is crucial to scrutinize the long-term impact of treatment. Many times, infection sets in and causes long-term damage. Peri-implantitis, peri-implant mucositis, and severe bone loss are all common defects with implants. Research shows that after five to 10 years, 80% of implants presented with peri-implant mucositis, and 12%–66% had peri-implantitis and tooth loss ranges between 3.6% and 13.4%.1 If this is the case, why are dental hygienists and dentists opting for implants when they could be implementing other therapies to preserve natural teeth, such as periodontal therapy and biofilm management?

What alternative therapies are available?

As a dental hygienist, it is vital to assess each client and find a treatment that is best for the individual. Significantly less-invasive procedures than dental implants are available, with prevention and early intervention being a top priority. These treatments can preserve teeth that were initially deemed useless and help to alleviate further interference with the teeth.

Prophylaxis—prevention and early intervention

An ideal way to prevent tooth loss is to catch any disease activity early. The term “bloody prophy” is thrown around these days to describe “cleanings” or “prophies” performed on patients who show obvious signs of bleeding and inflammation without intrusive intervention. Catching the early signs of inflammation plays a huge part in keeping natural teeth and preventing tooth loss, in addition to the systemic concerns that accompany chronic inflammation.

Protocols such as guided biofilm therapy5 (GBT)—using an eight-step systematic approach to manage biofilm and prevent or decrease inflammation—focus heavily on self-accountability with patients who are motivated to use products that fit their lifestyle and level of disease or health. These steps are less invasive and more effective at disrupting biofilm than traditional modalities.

Glycine’s6 “biocompatible organic salt crystals,” which dissipate when mixed with water, form a low level of abrasiveness on the teeth, resulting in less root damage and tissue abrasion compared to previously used powders such as sodium bicarbonate. Erythritol powder, a chemically neutral powder, is even less abrasive than glycine and also easily dissolvable in water.

Helping patients understand their role in preventing tooth loss is an essential part of the dental appointment. Focusing on correct assessment and diagnosis of the patient, using diagnostic tools such as disclosing solutions to stain the toxic biofilm, and finding the best home-care tools to motivate patients to take care of their mouths are all vital steps. It is time to stop accepting “just a little bleeding” during prophylaxis appointments and concentrate on actually preventing disease and saving natural teeth.

Periodontal therapy

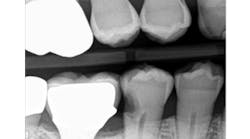

Periodontal therapy is more than frequent recall appointments.7 Yes, patients with periodontal disease require additional appointments, but the frequencies are determined by individual risk factors, including genetics, lifestyle habits, diet, and systemic diseases. Periodontal therapy or supportive maintenance takes a multifactorial approach, even for the dental hygienist. On completion of surgical or nonsurgical treatment, the clinician's goal is to help the patient maintain shallow periodontal pockets to prevent the need for retreatment (figure 2).8

Depending on the state in which you practice, dental hygienists can have multiple modalities at their disposal for use during supportive periodontal therapy. Lasers, endoscopes, and air powder procedures, such as AirFlow with a subgingival tip called PerioFlow, can help accomplish biofilm management during the patient’s appointment, in addition to using traditional instruments such as ultrasonic scalers and dental curettes.

It is important to approach supportive periodontal therapy as a team. Knowing when to refer, or, in a periodontal practice, knowing when the dental hygienist can no longer maintain the patient’s periodontal health is crucial. Utilizing materials such as enamel matrix protein derivative (EMD) can be a game changer in wound healing for periodontally involved teeth.9 A key factor in using materials such as EMD is catching patients early before too much bone has been lost. Hygienists and dentists must be aware of their supportive therapy limitations, understanding when to refer to give natural teeth a fighting chance.

There is an expense involved with saving natural teeth. However, it is essential to weigh the costs involved with the potential complications from tooth extraction and dental implants, such as bone augmentation and soft tissue management.1 Post dental implant placement, patients often feel they do not need to visit the dentist as frequently, but that is a fallacy. Implants can require a similar frequency for dental visits and potentially involve more home-care tools, demanding the same amount of time compared to treatment for retaining natural teeth with questionable prognoses.

Tools of the trade to save natural teeth

Remember that saving teeth and having successful, supportive periodontal therapy with multifactorial approaches, combined with biofilm management both in the office and at home, should be at the forefront of treatment planning and incorporated during the dental appointment (figure 3).

The patient’s responsibility in saving his or her teeth

Prevention is better than cure. A critical element in saving teeth and increasing disease prevention is ensuring that patients are involved in the care of their teeth. Regular brushing and cleaning of the teeth are essential for a healthy mouth. To minimize the impact of infection and discomfort for patients, dental hygienists should always assess each person's individual needs and respond to them based on the presentation of the patient’s teeth and his or her behavior toward ongoing self-care (figure 4).

Implants are not always in the best interests of our patients. To apply a discerning treatment plan, attention must be paid to patients’ behavior once they leave the clinic. The next time you go to pick up a scaler, first think how else you might be able to help your patient practice better habits for long-term health of the teeth. Though we have viable options for tooth replacement, saving and preserving these body parts—as we do with other organs in the body—should be a number one priority.

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in Perio-Implant Advisory, a chairside resource for dentists and hygienists that focuses on periodontal- and implant-related issues. Read more articles and subscribe to the newsletter.

References

1. Clark D, Levin L. In the dental implant era, why do we still bother saving teeth? Dent Traumatol. 2019;35(6):368-375. doi:10.1111/edt.12492

2. Loos BG, Needleman I. Endpoints of active periodontal therapy. J Clin Periodontol. In press. doi:10.1111/jcpe.13253

3. Razak PA, Richard KMJ, Thankachan RP, Hafiz KAA, Kumar KN, Sameer KM. Geriatric oral health: A review article. J Int Oral Health. 2014;6(6):110-116.

4. Miller N. Biofilm conquered: Glycine powder to the rescue! Oral Health website. https://www.oralhealthgroup.com/features/biofilm-conquered-glycine-powder-to-the-rescue/. Published May 28, 2019. Accessed February 11, 2020.

5. Deudon M. Guided biofilm therapy: Innovative prophylaxy. European Association for Osseointegration website. https://www.eao.org/page/Inspyred_61_06. Accessed February 6, 2020.

6. Sultan DA, Hill RG, Gillam DG. Air-polishing in subgingival root debridement: A critical literature review. J Dent Oral Biol. 2017;2(10):1065.

7. American Academy of Periodontology. Position paper guidelines for periodontal therapy. J Periodontol. 2001;72(11):1624-1628. doi:10.1902/jop.2001.72.11.1624

8. Matuliene G, Studer R, Lang NP, et al. Significance of periodontal risk assessment in the recurrence of periodontitis and tooth loss. J Clin Periodontol. 2010;37(2)191-199. doi:10.1111/j.1600-051X.2009.01508.x

9. Sculean A, Windisch P, Döri F, Keglevich T, Molnár B, Gera I. Emdogain in regenerative periodontal therapy: A review of the literature. Fogorv Sz. 2007;100(5):211-232.