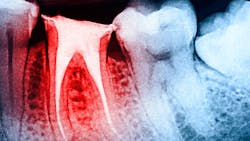

Pain after root canal therapy: Causes and considerations

Persistent tooth pain after root canal therapy can occur under several scenarios, and research suggests that between 4% and 6% of all teeth treated with root canals continue to be associated with lingering pain. Here are the three most common causes of pain that we see:

- The root canal was necessary, but as the expression of tooth pain is often a combination of nociception from both deep somatic tissues (the pulp) and musculoskeletal tissues (the PDL), pain in the tooth lingers as the removal of the infected or inflamed pulp during root canal treatment was insufficient or incomplete. Or, despite complete pulp removal, nociception from the PDL caused by long-standing or intense pulpal pathology or other impacts to the tooth persists after completion of the root canal.

- The root canal was necessary, but the act of taking out the dental pulp (an amputation event) led to neuropathic pain.

- The toothache was misdiagnosed, and the root canal was not necessary.

Let’s look at each scenario in more detail.

1. The root canal was necessary but did not solve the pain.

Complete removal of the diseased pulp is not achieved. Despite significant advancements in the delivery of root canal therapy to address tooth pain of deep somatic origin (the dental pulp), there are times when, as the result of the complexity of the root anatomy, challenges in providing complete anesthesia, managing patient comfort in the chair, and limited technical skill and experience of the provider, complete removal of the diseased pulp is not achieved.

As a result, pain continues, though the patient was advised that treatment was completed. In these scenarios, re-treatment of the tooth (often with the assistance of cone beam imaging and microscopic visualization if not used prior, or with a specialist) may be required to determine where the first treatment efforts fell short. Once addressed, these types of lingering pain problems mostly resolve.

Complete removal of the diseased pulp is achieved. At other times, technical success is fully achieved in removing the compromised dental pulp, but due to the chronicity of the pulpal compromise before removal or its origin (trauma/fractured tooth, etc.), nociception from an irritated or injured PDL is not turned off. The result is pain, which can be constant but often is most concerning while chewing. As a result, the patient totally avoids chewing on that side of the mouth.

More root canal therapy does not solve the problem and often creates more pain. If time and medications designed to quiet the PDL do not succeed after six to 12 months and the patient continues to avoid chewing on that side of their mouth to avoid pain, tooth extraction may be the best option.

2. The root canal was necessary, but neuropathic pain resulted.

We must remember that root canal therapy involves removing the tooth’s nerve. This is essentially an amputation. Just as a person who has a leg amputated may develop phantom limb pain (i.e., an ongoing sensation of pain in the limb even though it’s been lost), a patient may also develop “phantom tooth pain” after root canal therapy or tooth extraction. Fortunately, the incidence of phantom tooth pain after tooth loss is much lower than the incidence of phantom limb pain after arm or leg amputation.

In fact, as far back as the year 2000, when an article titled, “Phantom Tooth Pain: A New Look at an Old Dilemma”1 by Drs. Joseph Marbach and Karen Raphael was published in Pain Medicine, they noted: “Despite the fact that teeth are probably the most commonly amputated structures among members of industrialized societies, relatively little attention has been paid to this orofacial phantom pain.”

Now, 23 years later, phantom tooth pain is commonly characterized as a deafferentation pain disorder leading to persistent pain in teeth that have been denervated (by root canal) or pain in an area previously occupied by a tooth prior to extraction.

Deafferentation pain should be considered a type of neuropathic pain, now defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain as pain caused by a lesion or disease of the somatosensory nervous system.2 When nerves are cut or amputated, either intentionally or unintentionally, resulting in a loss of sensory input into the central nervous system, neuropathic pain can emerge.

In some classification systems, phantom tooth pain is now called post-traumatic trigeminal neuropathic pain, or PTTNP. Because these pain problems are not routinely seen by practicing dentists, practitioners still tend to treat lingering tooth or tooth site complaints with common treatment options to address what is thought to be a deep somatic pain problem (structural compromise/infection/inflammation). The result, however, is ongoing pain, often with neighboring innocent teeth being brought into the conversation. These are difficult problems at the outset that become more complex with the passing of time and failed treatment.

Clues that a PTTNP problem has emerged may include, during examination, the presence of:

- Allodynia: a painful response to normally nonpainful stimuli

- Hyperpathia: a painful response to repetitive, nonpainful stimuli

- Hyperalgesia: a lowered pain threshold to a painful stimulus

Once diagnosed, these problems are best treated with a variety of systemic medications, including gabapentinoids, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), and selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). The use of topical medications and neuromodulators such as Botox are also used to address these often stubborn and life-impacting problems.

3. The toothache was misdiagnosed, and the root canal was not necessary.

Along with true deep somatic toothache pains and those arising from neuropathic origins, many non-tooth-related conditions can cause pain to be perceived in the teeth. If a patient is suffering from one of these conditions, no amount of root canal therapy will relieve their pain.

Conditions that can cause tooth pain and prompt root canal therapy unnecessarily include:

- Referred muscle pain from the jaw or neck

- Orofacial “headache” attacks (e.g., orofacial migraine)

- Nerve pain (e.g., trigeminal neuralgia)

- Lyme disease

- Cardiovascular pathology

- Sinus infections

- Brain tumors

As these are uniquely different medical conditions, each can give rise to complaints of tooth pain, expressed with very different temporal and spatial patterns, variable intensities, quality, and duration when present. All of them, at one point in time, have prompted unsuccessful root canal treatment. With these types of scenarios, it is often all about careful history-taking and recognizing clues in the symptom presentation that often point to non-tooth-related sources of pain. Toothache pain prompted by speaking, physical exertion, coughing, positional changes in the head, or randomly for no good reason are just some of the clues that the orofacial pain specialist is adept at understanding.

When to consider a referral

If tooth pain persists after root canal therapy, there are certain lines of thinking to consider before moving forward with additional care. Referral to an orofacial pain specialist should be a consideration.

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in Perio-Implant Advisory, a chairside resource for dentists and hygienists that focuses on periodontal- and implant-related issues. Read more articles and subscribe to the newsletter.

References

- Marbach JJ, Raphael KG. Phantom tooth pain: a new look at an old dilemma. Pain Med. 2000;1(1):68-77. doi:10.1046/j.1526-4637.2000.00012.x

- IASP’s 50th anniversary: working together for pain relief throughout the world. International Association for the Study of Pain. https://www.iasp-pain.org/

About the Author

Donald R. Tanenbaum, DDS, MPH

Donald R. Tanenbaum, DDS, MPH, is a board-certified orofacial pain specialist who has dedicated his 40-year career to diagnosing and treating orofacial pain, TMD/TMJ, headache, and sleep-related breathing disorders. He believe every patient deserves compassion and personal attention. Dr. Tanenbaum is trusted by medical and dental specialists in nearly every discipline to care for their patients. He practices in Manhattan, Hauppauge, and Woodbury, New York, offices.

Updated February 5, 2024

John E. Dinan, DMD, MS

John E. Dinan, DMD, MS, is a board-certified orofacial pain specialist who treats TMJ conditions and other orofacial pain. A 10-year veteran of the US Air Force, he completed his orofacial pain training at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center. He is a diplomate of the American Board of Dental Sleep Medicine and an expert at providing dental devices for the treatment of snoring and sleep apnea. Dr. Dinan practices in New York City, New York, and Springfield, New Jersey.