One of the more common clinical scenarios that dentists who remove teeth in their dental practices experience is the management of patients who have alterations to their coagulation. Here, we will provide insight and valuable advice on how to handle patients who present with various medical issues involving the risk of bleeding.

Why do patients take anticoagulation medication?

Patients who have any of the following diseases will likely be taking anticoagulants:

- severe COVID-19 disease

- cancers

- factor V Leiden

- other blood clotting factor disorders

- diseases requiring hormone replacement therapy

- myeloproliferative disorders such as polycythemia vera

- obesity

- pregnancy

Further reading: Gum bleeding after a dental cleaning

Patients with these conditions can be more susceptible to blood clots and may require anticlotting medication.1 Patients can often be medically anticoagulated for reasons such as atrial fibrillation, cardiac stents, replaced heart valve, and/or other cardiac issues. Recently, those with severe COVID-19 have been experiencing hypercoagulation issues. This disease, termed COVID-19–associated hypercoagulopathy (CAC), has been noticed in emergency and intensive care units and in presenting patients who have been treated with anticoagulant medications.2 These medications are also used in individuals with hypercoagulation status to prevent deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, heart attack, and/or stroke. Because these medications prevent blood clots from forming, they also may cause excessive bleeding after trauma/surgery, including tooth extraction.

More rarely, patients can present with inherited coagulopathies, such as hemophilia, von Willebrand disease, or other blood clotting factor disorders that leave patients at increased risks of intra- and postoperative bleeding. These patients are not on anticoagulation medication but are still prone to excessive bleeding (figure 1).Appropriate perioperative management of the anticoagulated patient requires a basic understanding of the patient’s underlying medical history for which he or she is anticoagulated. Many patients will tolerate either a reduction or complete discontinuation of their anticoagulation medications for a limited time, allowing a more ideal environment in which to perform oral surgical procedures.

Pharmacology of common anticoagulation medications

Next, we must understand the basic pharmacology of the various forms of anticoagulation therapies. Not only is it important to understand the function of these medications, but also the effective half-lives that allow guidance on when to discontinue and when to resume these medications.3

Here is a list of common medications patients take for anticoagulation and their biokinetic pathways:

- Coumadin: Functions by blocking the extrinsic coagulation pathway and has an effective half-life of three days. If coumadin is going to be discontinued, we can expect that the patient’s coagulation process will be at an appropriate level three days after discontinuation.

- Aspirin or Plavix (clopidogrel): Interferes with platelet adhesion, is irreversible, and lasts the life of the blood platelet, thus these medications must be discontinued seven days prior to surgery if we are to expect normal platelet function.

- Eliquis (apixaban): Blocks factor X with a 12- to 24-hour half-life so this medication should be stopped 12 to 24 hours before surgery and resumed 12 hours after surgery once stable clotting has occurred.

- Pradaxa (dabigatran etexilate): Reversibly inhibits thrombin. Similar recommendations to Eliquis apply to this medication.

Further reading: Top 5 anatomical differences between dental implants and teeth that influence treatment outcomes

Management of patients with bleeding problems who require tooth extraction

Consultation with the patient’s physician to come up with the best perioperative management strategy is the first step to see if discontinuation of anticoagulant medications is warranted. With that in mind, there is always a risk of a thromboembolic event when the anticoagulation therapy is discontinued. Minor surgical procedures, such as three to four extractions or a dental implant, can usually be managed without the need to discontinue anticoagulants. For major surgery, patients will need to come off their medications and occasionally will need to be managed with a short-acting anticoagulant, such as Lovenox or heparin injections, which can then be stopped the night before surgery.Intraoperative techniques

Intraoperative techniques to be used after tooth extraction to help reduce the incidence of prolonged bleeding:

- Removal of all granulation tissue, as this tissue tends to increase bleeding even in patients who are not anticoagulated

- Laser cauterization of bleeding tissues

- Avoiding undue trauma or tears to soft tissues will help minimize unwanted bleeding.

- Good suctioning to make certain the extraction site is clean, followed by adequate irrigation

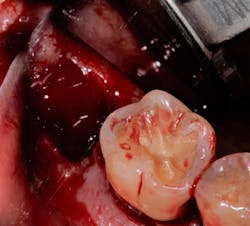

- Pack the socket with a hemostatic plug such as gel-foam, surgical, Avitene, collagen plug, or Helistat/HeliPlug (figure 2).

- Suture with primary closure.

- Direct gauze pressure for five to 10 minutes

Postoperative instructions

Postoperative instructions to follow that will limit excessive bleeding:

- Avoid hot foods or liquids that could lead to vasodilation and increase the risk of bleeding.

- Avoid rinsing the mouth for 24 hours as the mechanical pressure can loosen a clot and cause prolonged bleeding.

- Avoid smoking for 24 hours as the heat from cigarettes and the mechanics of smoking, which creates a negative pressure in the mouth, are both deleterious to stable clotting.

- Avoid crunchy or hard foods and seeds that can cause mechanical disruption of the clot.

- Avoid foods and liquids that can cause additional anticoagulation, such as foods with garlic and alcohol.

- Avoid supplements that can cause bleeding, such as ginkgo biloba, ginseng, ginger, and dong quai.

What to do for postoperative bleeding

Should the patient experience postoperative bleeding, there are some routine steps to try to promote hemostasis. First, bite down on gauze for 20 minutes. If the bleeding persists, ask the patient to moisten a tea bag in cool water, wrap that in a gauze, and bite for an additional 20 minutes. Tea contains tannic acid, which helps with clotting. If bleeding is persistent despite these measures, have the patient return to the dental office.

It is not uncommon for anticoagulated patients to form incomplete clots, commonly called “liver clots.” Often, the patient states that the bleeding begins and then discontinues, only to begin again after several hours. Management consists of local anesthesia with epinephrine, assuming the medical condition will allow, followed by irrigation of the faulty clot, suctioning, and then repacking and suturing to allow a more stable clot to form.

Once the patient has formed a stable clot, have them resume normal preoperative medications. By performing clean surgery, managing soft tissues appropriately, and packing and suturing the wounds, then having the patient follow standard postoperative measures, prolonged postoperative bleeding can be a rare occurrence.

References

- What is excessive blood clotting (hypercoagulation)? American Heart Association. https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/venous-thromboembolism/what-is-excessive-blood-clotting-hypercoagulation

- Waite AAC, Hamilton DO, Pizzi R, Ageno W, Welters ID. Hypercoagulopathy in severe COVID-19: implications for acute care. Thromb Haemost. 2020;120(12):1654-1667. doi:1055/s-0040-1721487

- Alquwaizani M, Buckley L, Adams C, Fanikos J. Anticoagulants: a review of the pharmacology, dosing, and complications. Curr Emerg Hosp Med Rep. 2013;1(2):83-97. doi:1007/s40138-013-0014-6

Originally published in 2015. Updated December 2021.

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in Perio-Implant Advisory, a chairside resource for dentists and hygienists that focuses on periodontal- and implant-related issues. Read more articles and subscribe to the newsletter.