Top 5 sources of dental implant pain when "there is nothing wrong with the implant"

Editor's note: Originally published in 2017. Formatting updated in 2024.

Ascertaining the etiology of a patient’s perceived pain post-dental implant placement when all clinical and radiographic parameters are within normal limits can be a daunting task. Clinical signs that could indicate pain from peri-implant tissue infection include bleeding upon probing, increased probing depths, suppuration, friable tissue, ulceration, etc. Radiographic evidence of problematic implants eliciting pain symptoms include radiolucent regions, mechanical failure of implant componentry, and violations of anatomy.

What should the course of action be, however, when all clinical signs are normal, and the patient’s only problem is the symptom of pain? This article will focus on factors that can elicit pain post-dental implant placement that are often elusive and obscure diagnosis unless a good knowledge base is present.

Further reading:

- Dental pain: Predicting postoperative pain prior to the procedure

- Tooth pain after root canal therapy: The 5 common causes

No. 1: Violations of the anterior loop of the inferior alveolar canal (IAC)

As the inferior alveolar nerve (IAN) approaches the mental foramen, the canal turns upward on the buccal side of the mandible.

The IAN emerges from the mental foramen and generates the mental nerve. The mental portion of the IAC can course straight, vertical, or in an anterior loop fashion. In the anterior loop, the nerve runs upward and courses toward mid-mandible before looping and heading back toward the mental foramen (figure 1).

The literature1 has reported variations in the prevalence of the anterior loop from 7%–88%, with a mean prevalence of around 28%.2 Trauma to this region (mandibular premolar-incisor) can induce sensory disturbances, increased bleeding, and pain post-implant therapy in a region otherwise known as a “safe area.”

A recent review suggested that the traditional thought of staying at least 2 mm away from the IAC should be revisited. This study looked at 60 patients with implants placed within 2 mm of the IAC. The authors noted that even if the dental implant was placed within .75 mm of the IAC, as long as direct transection or compression did not occur, the patient experienced no sensory disturbances.3

Taking a high-quality CBCT image may help with neural imaging and deciphering if an anterior loop is present.

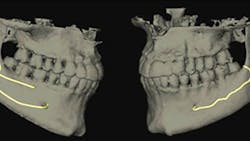

No. 2: Violations of a branch of a bifid or trifid mandibular canal

The IAC is typically described as a singular canal4 containing the neurovascular bundle that clinicians know not to violate, and a 2 mm “safety zone”5 has been described when placing dental implants. It is now known that multiple smaller branches of the IAC can occur that run parallel to the main trunk of the canal.6 Up to 40% of the nerve can branch off the main canal, and if these branches are large enough, a secondary or even tertiary canal can result (figure 2).

Multiple branches of the mandibular canal often go unrecognized, because many dentists are unaware of this anatomic variation even though the canals may be visible on a panoramic radiograph or CT scan. Violations of this secondary/tertiary canal resulting in pain post-implant placement have been described in the literature.7

No. 3: Inadequate keratinized tissue around the dental implant crown

There is no consensus in the literature regarding the need for adequate keratinized tissue around a dental implant (usually described as being at least 2 mm in width). Some studies have suggested, however, that a lack of keratinized tissue can lead to pain post-implant placement and/or restoration (figure 3).8

These symptoms are most notably elicited upon palpation by brushing, eating, and percussion. These symptoms can often be treated with the addition of a soft-tissue graft that enhances the keratinization of the tissue around the dental implant.

No. 4: Poor bone-to-implant contact (BIC)

Although an implant may seem to be surrounded by bone on a two-dimensional and even a three-dimensional radiograph and CT scan, that bone may be of poor quality and/or not completely intimate with the implant surface (figure 4).

Poor BIC can occur when fibrous tissue encapsulates the body of the implant, which is then layered with bone. Radiographically the implant appears as if the bone levels are normal, and clinically the implant may exhibit no signs of mobility; however, the patient still experiences dental pain. This can be evident especially when the implant is put into function with a healing abutment or loaded with a crown. A possible solution to detect poor BIC is the use of a

resonance frequency analysis machine that will give a digital reading of the strength of the implant-bone connection.

No. 5: Predisposing risk factors toward postoperative dental pain

There have been reports in the literature that certain risk factors can exist within the medical/genetic makeup that may predispose a patient to persistent pain post-implant therapy.9 These risk factors include fibromyalgia, temporomandibular disorders, visceral pain hypersensitivity disorders, chronic pain, depression/anxiety, etc. All of these factors can result in pain with unknown etiology. This type of pain is usually placed under the umbrella of “peripheral painful traumatic trigeminal neuropathy” (PPTTN).

In conclusion, there are many reasons a patient can have pain post-dental implant therapy, despite demonstrating the typical clinical and radiographic signs. It is easy to label this type of pain as having a psychosomatic origin, but further evaluation of all factors—including those previously described in this article—should be ruled out prior to a diagnosis such as this.

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in Perio-Implant Advisory, a chairside resource for dentists and hygienists that focuses on periodontal- and implant-related issues. Read more articles and subscribe to the newsletter.

References

1. Jacobs R, Mraiwa N, vanSteenberghe D, Gijbels F, Quirynen M. Appearance, location, course, and morphology of the mandibular incisive canal: an assessment on spiral CT scan. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2002;31(5):322-327. doi:10.1038/sj.dmfr.4600719

2. Sahman H, Sisman Y. Anterior loop of the inferior alveolar canal: a cone-beam computerized tomography study of 494 cases. J Oral Implantol. 2016;42(4):333-336. doi:10.1563/aaid-joi-D-15-00038

3. Froum SJ, Bergamini M, Reis N, et al. A new concept of safety distance to place implants in the area of the inferior alveolar canal to avoid neurosensory disturbance. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2021;41(4):e139-e146. doi:10.11607/prd.5626

4. White SC, Pharoah MJ. Oral Radiology: Principles and Interpretation. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Mosby; 2014.

5. Misch CE. Root form surgery in the completely edentulous mandible: Stage I implant insertion. In: Contemporary Implant Dentistry. 2nd ed. St Louis, MO: CV Mosby Co.; 1999:24.

6. Maqbool A, Sultan AA, Bottini GB, Hopper C. Pain caused by a dental implant impinging on an accessory inferior alveolar canal: a case report. Int J Prosthodont. 2013;26(2):125-126. doi:10.11607/ijp.3191

7. Aljunid S, AlSiweedi S, Nambiar P, Chai WL, Ngeow WC. The management of persistent pain from a branch of the trifid mandibular canal due to implant impingement. J Oral Implantol. 2016;42(4):349-352. doi:10.1563/aaid-joi-D-16-00011

8. Greenstein G, Cavallaro J. The clinical significance of keratinized gingiva around implants. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2011;32(8):24-31.

9. Delcanho R, Moncada E. Persistent pain after dental implant placement: a case of implant-related nerve injury. J Am Dent Assoc. 2014;145(12):1268-1271. doi:10.14219/jada.2014.210