Top 5 anatomical differences between dental implants and teeth that influence treatment outcomes

Although dental implants typically enjoy a high survival rate1 and have been a superior treatment option to replace missing or hopeless teeth, they are not without complications. The literature is filled with a variety of well-documented problems associated with implants in the biological and mechanical spheres.

Many of the existing therapies used to maintain and treat diseased implants have been developed from the treatment of natural teeth. However, because of the anatomical differences between teeth and dental implants,2 therapies that are successful in treating teeth may not enjoy the same success rate when used on diseased implants.

This article will highlight five anatomical differences between teeth and implants and describe how those differences can influence diagnosis and treatment.

Related reading:

No. 1: Periodontal sulcus versus peri-implant sulcus

Anatomical difference: Peri-mucosa is composed of keratinized oral epithelium, sulcular epithelium, and junctional epithelium, as well as the underlying connective tissue. This soft-tissue interface is made up of the epithelium and the underlying connective tissue, which includes a biologic zone known as the “biologic width” (the height of the attachment apparatus). The average dimension of 2.04 mm is comprised of supra-alveolar connective tissue and junctional epithelial attachment. But there is a difference between the implant surface and the epithelial cells with hemidesmosomes and basal lamina present, leading to deeper sulcus, compared to that found around natural teeth in a healthy situation. Additionally, in a healthy situation, a weaker sulcular attachment around implants allows movement of a periodontal probe through the biologic width until the probe contacts bone, and as such, it is not a reliable method of determining periodontal health with implants.

Clinical implication: Because the biologic width around implants is increased when compared with teeth, greater sulcular depths are to be expected.3 Normal physiological probing depths can be more than 4–5 mm around dental implants, whereas with teeth, increased pocket depths usually are diagnosed as pathologic. In addition, bleeding upon probing with dental implants may not always indicate disease, whereas bleeding upon probing around teeth usually indicates an increased inflammatory state.

More clinical tips:

No. 2: Periodontal attachment versus peri-implant attachment

Anatomical difference: Although natural teeth and implants have a connective tissue attachment with gingival tissue at the crest, this attachment differs. With natural teeth, the gingival fibers run perpendicular to the tooth’s long axis attaching to the tooth's surface, whereas with implants, the fibers run parallel to the implant’s long axis and do not attach to the implant’s surface. In addition, the natural tooth has nine different types of supracrestal fibers that enhance attachment while the dental implant has two at most. The connective tissue adhesion with implants has poor mechanical resistance compared with natural teeth.

Clinical implication: Because of differences in peri-implant and periodontal attachment, the likelihood of attachment breakdown when faced with bacterial challenge is greater with implants. Once the “implant seal” around the implant-attachment complex breaks down, exacerbation of tissue loss increases when compared with teeth. It becomes imperative that supportive periodontal treatment (i.e., cleanings) and home hygiene are reinforced to ensure long-term restoration.

No. 3: Inflammatory response

Anatomical difference: The fibers on natural teeth provide a physical barrier to bacterial invasion due to their perpendicular orientation apical to the periodontal ligament (PDL), limiting the progression of periodontal disease. This physical barrier is not present with implants, as the parallel orientation of the fibers allows the apical progression of bacteria ... leading to the potential for a more rapid spread of inflammation ... leading to peri-implantitis.

Clinical implication: When faced with a bacterial challenge, not only is the tissue around dental implants weaker than teeth, but the inflammatory response elicited by the bacteria is much greater. Inflammation from the host response has been shown to lead to further tissue breakdown, which, again, makes dental implants more susceptible to tissue and bone loss when challenged by plaque. Dental implants also exhibit an inflammatory response that can last longer and be more pervasive than natural teeth if left untreated.

No. 4: Healing response of tissue

Anatomical difference: The healing response of tissues around implants varies from those around natural teeth. Implants exhibit a poor gingival vascular supply compared with teeth. Small, clean, closed wounds heal more quickly than large wounds, which heal slowly and with significant scarring. Flapless surgery has an added benefit of providing a better vascular supply and retaining vitality of the supracrestal connective tissue around the implant compared with raised soft-tissue flaps, which can inadvertently lead to cutting and damaging of supraperiosteal vessels. Wounds on the surrounding mucosa following the flapless procedure are smaller, cleaner, and more closed than the mucosal wounds left from the flap procedure.

Clinical implication: Due to the decreased vascularity around implants compared with teeth, the healing after nonsurgical and/or surgical therapy is slower. Tissue regeneration around diseased implants is not as predictable as it is around teeth and thus may require additional growth factors, proteins, and/or stem cells added to conventional regenerative biomaterials.

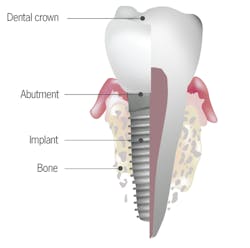

No. 5: Tooth root versus implant body

Anatomical difference: A periodontal ligament acts as a suspension system, transferring occlusal loads to the surrounding bone and allowing micromovement to dissipate limited overloads. Implants do not have periodontal ligaments; therefore, occlusal loads are directly transferred to the bone. Bone loss may result when overload presents over time, especially in off-axis directions. The periodontal ligament enables the tooth to manage these off-axis loads. Low continuous loads may cause orthodontic drifting of the tooth, which eliminates off-axis load. Implants, lacking a periodontal ligament, cannot orthodontically move to dissipate loads under normal circumstances. Consequently, stresses are concentrated in the bone, resulting in bone loss.

Clinical implication: Without a functional periodontal ligament, implants do not deal with off-axis loading as well as teeth do.4 Implants, therefore, are more likely to have mechanical complications5—such as screw loosening, fracture, and bone necrosis—when excessive parafunctional loads are applied. In addition, because of the porous, rough surface of most implants, bacterial contamination of the implant body versus the root surface is higher.6 Detoxification of the implant body prior to tissue regeneration around diseased implants is extremely important when resolving infections around dental implants. The level of detoxification of the natural root surface needed prior to guided tissue regeneration is still controversial in the literature. Finally, because the implant body is made of titanium or titanium alloy, a recently described process of tribocorrosion has been discussed in the literature. Tribocorrosion is the process of corrosion and breakdown of the dental implant body due to stresses from the oral environment. These particles embed themselves in the surrounding tissue and can elicit an inflammatory reaction causing tissue loss around the dental implant. A natural tooth root is not susceptible to tribocorrosion.7

References

- Degidi M, Nardi D, Piattelli A. 10-year prospective cohort follow-up of immediately restored XiVE implants. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2016;27(6):694-700. doi: 10.1111/clr.12642.

- Dhir S, Mahesh L, Kurtzman GM, Vandana KL. Peri-implant and periodontal tissues: a review of differences and similarities. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2013;34(7):e69-75.

- Cochran DL, Hermann JS, Schenk RK, Higginbottom FL, Buser D. Biologic width around titanium implants. A histometric analysis of the implanto-gingival junction around unloaded and loaded nonsubmerged implants in the canine mandible. J Periodontol. 1997;68(2):186-198.

- Passanezi E, Sant’Ana AC, Damante CA. Occlusal trauma and mucositis or peri-implantitis? J Am Dent Assoc. 2017;148(2):106-112. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2016.09.009.

- Stimmelmayr M, Groesser J, Beuer F, et al. Accuracy and mechanical performance of passivated and conventional fabricated 3-unit fixed dental prosthesis on multi-unit abutments. J Prosthodont Res. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jpor.2016.12.011.

- Han A, Tsoi J, Rodrigues FP, Leprince JG, Palin WM. Bacterial adhesion mechanisms on dental implant surfaces and the influencing factors. Int J Adhes Adhes. 2016;69, 58.

- Kheder W, Al Kawas S, Khalaf K, Samsudin AR. Impact of tribocorrosion and titanium particles release on dental implant complications - a narrative review. Jpn Dent Sci Rev. 2021;57:182-189. doi:10.1016/j.jdsr.2021.09.001

Originally published in 2017. Updated in 2021.

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in Perio-Implant Advisory, a chairside resource for dentists and hygienists that focuses on periodontal- and implant-related issues. Read more articles and subscribe to the newsletter.

About the Author

Scott Froum, DDS

Editorial Director

Scott Froum, DDS, a graduate of the State University of New York, Stony Brook School of Dental Medicine, is a periodontist in private practice at 1110 2nd Avenue, Suite 305, New York City, New York. He is the editorial director of Perio-Implant Advisory and serves on the editorial advisory board of Dental Economics. Dr. Froum, a diplomate of both the American Academy of Periodontology and the American Academy of Osseointegration, is a volunteer professor in the postgraduate periodontal program at SUNY Stony Brook School of Dental Medicine. He is a PhD candidate in the field of functional and integrative nutrition. Contact him through his website at drscottfroum.com or (212) 751-8530.

Gregori M. Kurtzman, DDS, MAGD, FPFA, FACD, DICOI, DADIA, DIDIA

Gregori M. Kurtzman, DDS, MAGD, FPFA, FACD, DICOI, DADIA, DIDIA, is in private general dental practice in Silver Spring, Maryland. He is a prolific author and has lectured internationally on the topics of restorative dentistry, endodontics, implant surgery and prosthetics, removable and fixed prosthetics, and periodontics. Dr. Kurtzman is a consultant and evaluator for multiple dental companies. He can be reached at [email protected].