Editor's note: Originally published December 6, 2016. Formatting updated November 7, 2022.

Background

Halitosis, also commonly known as “bad breath,” is a concern of many patients seeking help from health-care professionals. Although halitosis is usually an odor that is associated with the mouth, a person is more likely to contact a primary care medical doctor for diagnosis and management even though there is a significant dental component involved. Most physicians and dental practitioners are inadequately informed about the causes and treatments of halitosis.

READ MORE: Predictable halitosis treatment: Using microbial testing and antibiotic rinse therapy

This ambiguity is also exacerbated by a dearth of scientific data on halitosis due to factors such as cultural/racial differences as to what constitutes odor, investigator bias, and an absence in uniform testing measurements regarding organoleptic and mechanical measurements. In addition, there is no universally accepted definition of halitosis. Few studies document the prevalence of halitosis in population-wide or community-based samples. In the general population, halitosis has a prevalence of about 50% of subjects tested in the United States.1 In some studies, there was an increased correlation between older age and malodor with aging resulting in greater intensity of the odor. This article will briefly discuss the etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of halitosis.

Etiology of halitosis

Morning breath (physiologic halitosis) is caused by stagnation of saliva, entrapment of food particles, and presence of bacteria on the dorsum of the tongue due to the decrease in salivary movement during sleep.

Dental origin (intraoral)—75% of all cases2

- Periodontal/peri-implant problem

- Tooth problem

- Soft-tissue problems

- Dry mouth problems

Medical origin (extraoral)—20% of all cases3

- Gastrointestinal disorders

- Respiratory disorders

- Immunocompromised

- Autoimmune disorders

- Liver failure, renal failure

- Hormone fluctuation: menstruation

- Metabolic disorders

Imaginary halitosis or delusional halitosis is a condition in which a subject believes that his or her breath odor is offensive despite any verification by a clinician or confidant. In one study, 28% of patients complaining of bad breath did not show signs of bad breath.4

Diagnosing halitosis

Organoleptic tests5

- Smell the exhaled air of the mouth and nose, and compare the two. Odor detectable from the mouth but not from the nose is likely to be of oral or pharyngeal origin. Odor from the nose alone is likely to be coming from the nasal passages and/or sinuses.

- The wrist lick test—the patient licks the wrist and allows it to dry up for 10 seconds, after which the judge allots a score to it. Scraping from the tongue using a tongue blade/tongue scraper can also be tested.

- Floss can be used in the interproximal regions of the teeth from different areas of the mouth and judged as well.

Mechanical tests6

- Gas chromatography (GC) is highly specific to volatile sulfur compounds (VSCs) and can detect odorous molecules even in low concentrations. The problem with using this as a sole analysis of halitosis is that GC is only sensitive to sulfur-containing compounds. As oral malodor may comprise agents other than VSCs, this test may provide an inaccurate assessment.

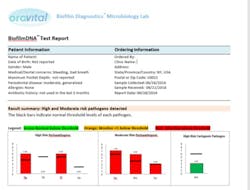

- DNA PCR test is a DNA analysis of salivary, subgingival, and tongue samples taken via paper points and a wiping pad to provide a whole mouth picture (see chart below). This test identifies the following bacteria:

1. Red complex (very virulent and pathogenic bacteria): Treponema denticola, Porphyromonas gingivalis, and Tannerella forsythia.

2. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans: Aggressive bacteria that have been implicated in aggressive destructive periodontitis.

3. Orange complex: Peptostreptococcus micros and Fusobacterium nucleatum, key components of pathogenic biofilm.

4. Streptococcus mutans: A species of bacteria that are responsible for the initiation of carious lesions.

5. Candida albicans: This fungus is frequently detected along with heavy infection by S. mutans in plaque biofilms and may be responsible for severe caries. It also forms a reservoir in the oral cavity that leads to candidiasis and other fungal lesions in the soft tissue. This species is also detected at peri-implantitis sites co-colonized with other pathogens.

Treatment

The available methods of halitosis treatment can be divided into these categories: mechanical reduction of microorganisms, chemical reduction of microorganisms, use of masking products, and chemical neutralization of VSCs. Etiology of halitosis is extremely important in order to determine if medical intervention is needed to treat systemic issues in addition to addressing the dental component.

Dental7

Mechanical removal of biofilm and microorganisms is the first step in the control of halitosis. This includes:

1. Addressing all cavities, exposed or damaged crowns, fractured teeth, crowded teeth, partially impacted teeth, and/or other areas that trap food.

2. Providing professional cleaning with scaling the teeth and root planing the roots to remove pathogenic bacteria. If bacterial issues are not resolved with scaling, further periodontal therapy may be needed.

3. Using tongue scrapers.

4. Providing interdental cleaning: GUM Soft-Piks (Sunstar Americas), Waterpik products (Water Pik Inc.), interdental flossers, dental floss, and/or any other interproximal agent can be used. A proprietary antibacterial cream can be used as an adjunct (OraVital FM3 cream).

5.Using a proprietary antibacterial mouth-rinsing agent for two to three weeks to reduce anaerobic bacteria (OraVital FM4 +/- amoxicillin). This is followed by chlorhexidine (CHX) for two weeks to repopulate with Eubacteria (good bacteria).

6. Using a toothpaste with triclosan, using essential oils, and consuming tablets with the probiotic Lactobacillus salivarius.

7. Using proprietary take-home trays (Perio Protect) to decrease the bacterial load and VSCs that are the source of oral malodor. These customized trays are combined with hydrogen peroxide gel and can be used two to three times a day with the added side effect of tooth whitening.

The use of masking agents—such as rinsing products, sprays, toothpaste containing fluoride, mint tablets, or chewing gum—only have a short-term masking effect. Xylitol agents, Biotene rinses, and systemic drugs—such as Evoxac (cevimeline) and Salagen (pilocarpine)—can increase salivation, which is useful because dry mouth may result in halitosis.

A patient’s diet is another factor that should be discussed when recommending a plan to combat oral malodor. Long intervals between eating or eating only once a day can have a negative effect on breath. Food such as garlic, onions, and other spices embed themselves in the tongue and can have long-lasting halitosis effects. The patient should also be instructed to quit smoking and avoid tobacco products and heavy use of alcohol.

Systemic

Systemic removal of microorganisms (extraorally) is needed if the source of halitosis is not in the mouth. Specific investigations should be carried out to isolate the source. Pharmacologic intervention can include broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage for pharyngitis and/or drugs such as proton pump inhibitors for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).8 When Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infections are observed, therapy consists of the intake of omeprazole, amoxicillin, and clarithromycin. Surgical intervention can include tonsillectomy/adenotonsillectomy, sinus surgery, or liver/kidney transplantation. In the cases of endocrinological and metabolic disorders (diabetes/amino acid disorders), the underlying diseases should be treated.

Psychological

Patients suffering from halitosis have significantly elevated scores for obsessive-compulsive symptoms, depression, anxiety, phobic anxiety, and paranoid ideation compared to similar patients without halitosis. A multidisciplinary approach of health-care practitioner, psychologists, and psychiatrist are required to treat delusional halitosis.

In conclusion

Due to the multifactorial complexity of halitosis, patients should be treated individually, rather than categorized. Diagnosis and treatment needs to be a multidisciplinary approach involving the primary health-care clinician, dentist, an ENT (ear, nose, throat) specialist, nutritionist, gastroenterologist, and clinical psychologist.

References

- Miyazaki H, Sakao S, Katoh Y, Takehara T. Correlation between volatile sulphur compounds and certain oral health measurements in the general population. J Periodontol. 1995;66(8):679-684.

- Wilhelm D, Himmelmann A, Axmann EM, Wilhelm KP. Clinical efficacy of a new tooth and tongue gel applied with a tongue cleaner in reducing oral halitosis. Quintessence Int. 2012;43(8):709-718.

- Kim JG, Kim YJ, Yoo SH, et al. Halimeter ppb levels as the predictor of erosive gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gut Liver. 2010;4(3):320-325. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2010.4.3.320.

- Iwu CO, Akpata O. Delusional halitosis. Review of the literature and analysis of 32 cases. Br Dent J. 1990;168(7):294-296.

- Greenman J, Duffield J, Spencer P, et al. Study on the organoleptic intensity scale for measuring oral malodor. J Dent Res. 2004;83(1):81-85.

- Salako NO, Philip L. Comparison of the use of the Halimeter and the Oral Chroma in the assessment of the ability of common cultivable oral anaerobic bacteria to produce malodorous volatile sulfur compounds from cysteine and methionine. Med Princ Pract. 2011;20(1):75-79. doi: 10.1159/000319760.

- Froum SJ, Rodriguez Salaverry K. The dentist’s role in diagnosis and treatment of halitosis. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2013;34(9):670-675.

- Kinberg S, Stein M, Zion N, Shaoul R. The gastrointestinal aspects of halitosis. Can J Gastroenterol. 2010;24(9):552-556.