Can periodontal disease be a contributing factor for COVID-19 severity?

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), leads to a life-threatening pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). The mortality rate from COVID-19 ARDS can approach 40%–50%.1 In addition to death due to pneumonia, the virus has been found to cause a hyperinflammatory state with the release of immune modulators and mediators.2 This has been described as a “cytokine storm” that has been found to cause cardiomyopathy, disseminated blood clots, stroke via large vessel occlusion, neurologic problems, thrombosis, and multiorgan failure, including heart, kidney, and brain.3 COVID-19 illness can range from mild to severe.

Disease severity has been attributed to many patient-related medical risk factors. In one of the largest cohort studies to date on 5,700 patients who entered the New York hospital system, Richardson et al. (2020) found that the top risk factors of people with severe COVID-19 symptoms included diseases associated with inflammation, such as hypertension (56.6%), obesity (41.7%), and diabetes (33.8%).4 Because of the increase in the severity of COVID-19 symptoms associated with patients who have preexisting inflammatory conditions, anti-inflammatory medications used to treat chronic/autoimmune inflammatory diseases have also been used to treat those with COVID-19.5

Periodontal disease is an inflammatory disease in which microbial etiologic factors induce a series of host responses that mediate inflammatory events, leading to tissue destruction in susceptible individuals.6 The purpose of this article is to highlight common inflammatory mediators between periodontal disease and COVID-19, and further suggest that periodontal disease may be a contributing factor and/or exacerbate COVID-19 severity.

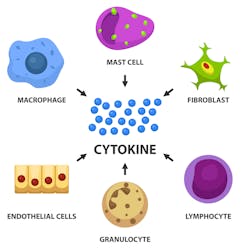

COVID-19–related morbidity and mortality have been attributed to an exaggerated immune response. The role of complement activation and its contribution to illness severity is increasingly being recognized, and the term cytokine storm (CS) has been associated with the disease progression of COVID-19. CS is a hyperactive immune response characterized by the release of interferons, interleukins (IL), tumor-necrosis factors (TNF), chemokines, and several other mediators that can lead to dysregulation in the immune system and organ shutdown. CS implies that the levels of released cytokines are injurious to host cells. TheseLaboratory results from clinical studies and autopsies on COVID-19 patients show elevated inflammatory markers, especially with the cytokines IL-6, IL-8, and TNFα. Anti-inflammatory therapeutic treatments—such as IL-6 inhibitors, high-dose corticosteroids, and monoclonal antibody drugs that have been used to treat patients with chronic inflammatory conditions—are now being repurposed to treat COVID-19 disease.7 In addition, physicians have advocated for the control of diabetes, hypertension, and weight loss to make patients less susceptible to severe symptoms if contracting COVID-19.8

These same cytokines and chemokines are also involved in both the physiology and pathology of bone metabolism.9 They are essential signals for the migration of osteoblast and osteoclast precursors, and, consequently, as potential modulators of bone homeostasis. Similar to the exacerbation of COVID-19 by the dysregulation of the immune system during the cytokine storm, disruption of the balance between osteoblast and osteoclast activities by periodontal bacterial products and host inflammatory cytokines is the main underlying cause of inflammation-induced periodontal bone loss.10

Could these same elevated inflammatory by-products seen during periodontal disease (i.e., IL-6, MAC-1, IL-8, and TNFα) exacerbate or contribute to the severity of symptoms experienced with COVID-19?11 If physicians advocate the medical control of diabetes, hypertension, and obesity as a means of disease pathogenesis, could the control of oral inflammation and periodontal disease help to protect patients against COVID-19 progression?

Studies have shown that periodontal treatment can lower overall systemic inflammatory markers.12 If inflammation can be lowered with periodontal treatment, can this type of oral care play a role in decreasing host susceptibility to COVID-19? In addition to common inflammatory pathways, a recent review has suggested that oral disease may exacerbate COVID-19 severity via two additional mechanisms.13 Periodontopathic bacteria have been implicated in aspirational pneumonia and an increase in viral respiratory infection.14 Furthermore, respiratory diseases, such as those caused by COVID-19, predispose patients to bacterial superinfections that complicate disease treatment. Oral bacteria have been implicated in those bacterial superinfections.

Can dental treatment decrease the likelihood of developing these superinfections? Controlled studies examining these common inflammatory and pathogenic pathways between periodontal disease and COVID-19 need to be performed to determine the final answers.

Editor's note: Join us for the not-to-miss Perio-Implant Advisory Symposium on October 23, 2020. In this important virtual meeting, you’ll learn the newest skills it takes to save patients’ natural dentition. Bring your team and transform your practice. Conference schedule and special rates available at this link. Presented by Geistlich Biomaterials.

Related articles

- The importance of periodontal treatment in post–COVID-19 dentistry

- Vitamin D and COVID-19 disease severity: An old ally in a new war

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in Perio-Implant Advisory, a newsletter for dentists and hygienists that focuses on periodontal- and implant-related issues. Perio-Implant Advisory is part of the Dental Economics and DentistryIQ network. To read more articles, visit perioimplantadvisory.com and subscribe at this link.

References

- Qin C, Zhou L, Hu Z, et al. Dysregulation of immune response in patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis. Published online March 12, 2020. 2020;ciaa248. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa248

- Tay MZ, Poh CM, Rénia L, MacAry PA, Ng LFP. The trinity of COVID-19: immunity, inflammation and intervention. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20(6):363-374. doi:10.1038/s41577-020-0311-8

- Rapkiewicz AV, Mai X, Carsons SE, et al. Megakaryocytes and platelet-fibrin thrombi characterize multi-organ thrombosis at autopsy in COVID-19: a case series. EClinicalMedicine 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100434

- Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA; 2020;323(20):2052-2059. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.6775

- Schett G, Sticherling M, Neurath MF. COVID-19: risk for cytokine targeting in chronic inflammatory diseases? Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20(5):271-272. doi:10.1038/s41577-020-0312-7

- Taubman MA, Kawai T. Involvement of T-lymphocytes in periodontal disease and in direct and indirect induction of bone resorption. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2001;12(2):125-135. doi:10.1177/10454411010120020301

- Jahanshahlu L, Rezaei N. Monoclonal antibody as a potential anti-COVID-19. Biomed Pharmacother. Published online June 4, 2020. 2020;129:110337. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110337

- Zhu L, She ZG, Cheng X, et al. Association of blood glucose control and outcomes in patients with COVID-19 and pre-existing type 2 diabetes. Cell Metab. 2020;31(6):1068-1077.e3. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2020.04.021

- Cekici A, Kantarci A, Hasturk H, Van Dyke TE. Inflammatory and immune pathways in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease. Periodontol 2000. 2014;64(1):57-80. doi:10.1111/prd.12002

- Yumoto H, Nakae H, Fujinaka K, Ebisu S, Matsuo T. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) and IL-8 are induced in human oral epithelial cells in response to exposure to periodontopathic Eikenella corrodens. Infect Immun. 1999;67(1):384-394.

- Liu YCG, Lerner UH, Teng YTA. Cytokine responses against periodontal infection: protective and destructive roles. Periodontol 2000. 2010;52(1):163-206. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0757.2009.00321.x

- Górski B, Górska R. The impact of periodontal treatment on inflammatory markers and cellular parameters associated with atherosclerosis in patients after myocardial infarction. Cent Eur J Immunol. 2018;43(4):442-452. doi:10.5114/ceji.2018.81356

- Sampson V, Kamona N, Sampson A. Could there be a link between oral hygiene and the severity of SARS-CoV-2 infections? Br Dent J. 2020;228(12):971-975. doi:10.1038/s41415-020-1747-8

- Okuda K, Kimizuka R, Abe S, Kato T, Ishihara K. Involvement of periodontopathic anaerobes in aspiration pneumonia. J Periodontol. 2005;76(suppl 11):2154-2160. doi:10.1902/jop.2005.76.11-S.2154

About the Author

Scott Froum, DDS

Editorial Director

Scott Froum, DDS, a graduate of the State University of New York, Stony Brook School of Dental Medicine, is a periodontist in private practice at 1110 2nd Avenue, Suite 305, New York City, New York. He is the editorial director of Perio-Implant Advisory and serves on the editorial advisory board of Dental Economics. Dr. Froum, a diplomate of both the American Academy of Periodontology and the American Academy of Osseointegration, is a volunteer professor in the postgraduate periodontal program at SUNY Stony Brook School of Dental Medicine. He is a PhD candidate in the field of functional and integrative nutrition. Contact him through his website at drscottfroum.com or (212) 751-8530.