Vitamin D deficiency: Impact on wound healing and implant failure

Vitamin D in its inactive form (vitamin D3 or cholecalciferol) is a steroid hormone that is synthesized in the skin with adequate exposure to the sun (ultraviolet light) and/or acquired through diet (figure 1). Vitamin D is a key player in bone growth and metabolism as it promotes the intestinal absorption of calcium and phosphorous. Additionally, vitamin D is vital for the health of the brain, cardiovascular system, respiratory tract, skin, and the immune and endocrine systems.

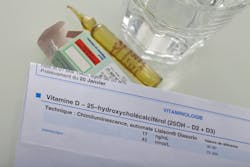

It also plays an important role in the dental field in the development of teeth, promotion of the immune response to oral microbial infections, and healing after periodontal, oral, and implant surgery. It is estimated that vitamin D insufficiency and deficiency have a prevalence as high as 50%–75% in the United States alone (especially during the winter months) and has been associated with numerous dental treatment complications.1 This article will briefly review the causes of vitamin D deficiency and its impact on dental treatment.Vitamin D is considered deficient when serum 25(OH) levels are <10 ng/mL, insufficient when serum levels are 10–30 ng/mL, and optimal with serum levels >30 ng/mL. Many commercially available tests can be used to test vitamin D levels (figure 2).

Causes of vitamin D deficiency

Vitamin D deficiency is mainly due to three causes:

- Diet—Most natural sources of vitamin D are animal based. Foods such as fatty fish (salmon and mackerel), fish oil, egg yolks, fortified milk/orange juice, and beef liver are high in this vitamin. Approximately 90 IU of vitamin D may be absorbed from food every day without the consumption of supplements.2 People who are strict vegans or lack intake of these foods need to find alternative sources to remain sufficient in this vitamin.

- Sun exposure—The human body synthesizes approximately 10,000 IU of vitamin D from tanning under natural sunlight until light redness of the skin. The recommended dosage of vitamin D may be absorbed by exposing the face, hands, and palms to natural sunlight two to three times a week. The common thought in the medical community is that one only needs to be in the sun for half the time it takes for the skin to turn pink. In other words, if it takes 30 minutes for the skin to start to turn red, only 15 minutes of sun exposure is necessary to receive adequate vitamin D intake. Individuals who live in climates with little sunlight, have inadequate sun exposure, have dark pigmented skin, and/or wear high SPF in the sun may have to supplement to achieve adequate vitamin D levels.

- Medical history—Vitamin D is converted to its active form in the kidneys, so people with kidney disease can be at risk for deficiency. In addition, certain intestinal diseases—e.g., celiac disease, cystic fibrosis, and Crohn’s disease—limit the amount of vitamin D absorption, leading to deficiency. Finally, obese individuals with a body mass index greater than 30 can have low levels of vitamin D as adipose cells extract vitamin D from the blood.3

Effect on dental treatment

Infection—It is well known that vitamin D deficiency can impair the immune response to oral microbial infections, increasing the risk of oral infections and periodontitis. The antimicrobial protein synthesis by immune and epithelial cells as well as nonspecific immune responses are activated by vitamin D.4 Vitamin D also takes part in the specific immune response and suppresses the destructive effects of chronic periodontitis.

Bone metabolism—Vitamin D plays an important role in the metabolism of bone. In the bone, vitamin D stimulates the activity of osteoclasts and increases the production of extracellular matrix proteins by osteoblasts. Deficient vitamin D levels have been correlated with low bone density, pathologic fracture, and poor bone healing after dental surgery.5 In addition, case reports have suggested that low vitamin D levels can be correlated with failure of bone grafts and regenerative materials.6

Periodontium—Because vitamin D has antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory effects, it has been shown that patients with low levels are more susceptible to developing gingival and periodontal disease. Because of the vitamin’s positive influence on bone metabolism, periodontal patients with low levels of vitamin D have also demonstrated poor responses to periodontal surgery. Studies have shown that patients with a vitamin D deficiency in blood plasma have worse results (i.e., lower tissue attachment level and probing depth change) after periodontal surgery. To improve postsurgical results in cases where periodontal treatment has failed, the authors of these studies advise testing vitamin D levels in the patient’s blood prior to the treatment and, if necessary, administer supplements.7

Dental implants—Since osseointegration of dental implants depends on bone metabolism, there is a possibility that low levels of vitamin D in the blood can negatively affect healing processes and new bone formation on the implant surface. The relationship between serum levels of vitamin D and osseointegration of dental implants is controversial and has been evaluated in a few case reports and animal studies. Most studies suggest that adequate serum levels of vitamin D can enhance the healing of peri-implant bone tissue.

One recent retrospective clinical study investigated the correlation between low serum levels of vitamin D and early dental implant failure. This study evaluated 885 patients who had been treated with 1,740 fixtures. Patients with vitamin D deficiency (serum levels of vitamin D <10 ng/mL) showed an early implant failure rate of 11.1%, compared to a failure rate of 2.9% in patients with normal levels of the vitamin (>30 ng/mL).8 The authors concluded that in cases of unknown failure, serum levels of vitamin D should be examined, and the operator may be advised to administer vitamin D weeks to months prior to implant surgery (figures 3 and 4).

Treatment

The first step for dental care providers when treating patients who lack vitamin D is to diagnose the patient as deficient, insufficient, or normal. According to the 2011 vitamin D dietary intake recommendations from the National Academy of Medicine, an intake of 600–800 IU of vitamin D would meet the nutritional needs for the majority of the population. In the past, some practitioners had advocated for the upper limits of 4,000–10,000 IU a day for individuals deficient in vitamin D, but those recommendations have recently been challenged. The latest research has shown that individuals taking 10,000 IU a day had lower bone mineral densities and increased bone resorption.9

The conclusion of these studies suggests that once a certain level of vitamin D has been reached, taking excess doses has either no or harmful effects. Treatment should be customized for the patient with specific serum testing and coordinated with his or her medical doctor.

Conclusion

Deficiency in vitamin D can lead to reduced bone mineral density, osteoporosis, bone fracture, the progression of periodontal diseases, and possible dental implant failure. Adequate intake of vitamin D can decrease the risk of gingivitis and chronic periodontitis, as it has been shown to have antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and pro-wound healing effects.

In addition, vitamin D is important for bone metabolism, alveolar bone resorption, preventing tooth loss, and promoting bone formation around dental implants. Patients who demonstrate a poor wound healing response after dental treatment—including healing after oral, periodontal, and implant surgery—should have vitamin D serum levels evaluated and treated if necessary.

References

1. Ginde AA, Liu MC, Camargo CA. Demographic differences and trends of vitamin D insufficiency in the US population, 1988–2004. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(6):626-632. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2008.604.

2. Institute of Medicine. Ross AC, Taylor CL, Yaktine AL, Del Valle HB, eds. Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. doi:10.17226/13050.

3. Khosravi ZS, Kafeshani M, Tavasoli P, Zadeh AH, Entezari MH. Effect of vitamin D supplementation on weight loss, glycemic indices, and lipid profile in obese and overweight women: a clinical trial study. Int J Prev Med. 2018;9(1):63. doi:10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_329_15.

4. Schwalfenberg GK. A review of the critical role of vitamin D in the functioning of the immune system and the clinical implications of vitamin D deficiency. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2011;55(1):96-108. doi:10.1002/mnfr.201000174.

5. Reid IR. Vitamin D effect on bone mineral density and fractures. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2017;46(4):935-945. doi:10.1016/j.ecl.2017.07.005.

6. Choukroun J, Khoury G, Khoury F, et al. Two neglected biologic risk factors in bone grafting and implantology: high low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and low serum vitamin D. J Oral Implantol. 2014;40)1)110-114. doi:10.1563/AAID-JOI-D-13-00062.

7. Bashutski JD, Eber RM, Kinney JS, et al. The impact of vitamin D status on periodontal surgery outcomes. J Dent Res. 2011;90(8):1007-1012. doi:10.1177/0022034511407771.

8. Mangano FG, Oskouei SG, Paz A, Mangano N, Mangano C. Low serum vitamin D and early dental implant failure: is there a connection? A retrospective clinical study on 1740 implants placed in 885 patients. J Dent Res Dent Clin Dent Prospects. 2018;12(3):174-182. doi:10.15171/joddd.2018.027.

9. Burt LA, Billington EO, Rose MS, Raymond DA, Hanley DA, Boyd SK. Effect of high-dose vitamin D supplementation on volumetric bone density and bone strength: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;322(8):736-745. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.11889.

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in Perio-Implant Advisory, a newsletter for dentists and hygienists that focuses on periodontal- and implant-related issues. Perio-Implant Advisory is part of the Dental Economics and DentistryIQ network. To read more articles, visit perioimplantadvisory.com, or to subscribe, visit dentistryiq.com/subscribe.