Bone grafting after tooth removal: Why, when, and what to use [video]

Why?

Tooth extraction is a common practice in the United States, with a prevalence of roughly 50% of adults in the age range 20–64 having at least one tooth extracted. (1) The normal pattern of bone healing post-tooth extraction is resorptive, typically leaving both hard- and soft-tissue defects in the alveolus without site preservation and/or tissue grafting. (2) This is problematic as loss of tissue structure in the jaw directly affects the functional and esthetic outcomes of dental implants, as well as tooth-borne fixed prosthetics (dental bridges).

Although unpredictable, a greater amount of alveolar ridge loss following extraction usually occurs in the horizontal dimension and affects the buccal bone of the ridge. (3) In fact, 50% of alveolar bone dimension can be lost after tooth extraction, with losses reported of up to 6–7 mm (figure 1). Two-thirds of this loss of bone volume can occur within the first three months of tooth extraction. (4)

Loss of vertical ridge height can also occur and usually takes place along the buccal aspect of the ridge to a lesser degree than horizontal ridge loss. (5) Corresponding reductions in vertical ridge height ranging from 2–4 mm have been noted. (6) The combination of this resorptive pattern results in a ridge that has moved in a palatal/lingual direction and has atrophied vertically (figure 1a).

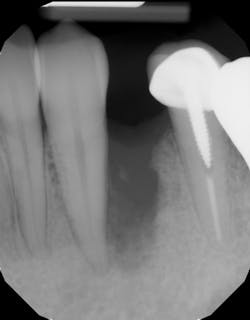

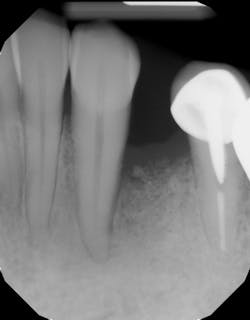

These alveolar bone changes often compromise implant placement due to thin bone volume (figures 2a–2d).

Reduction in quantity and quality of bone can also compromise functional and esthetic outcomes of both implants and fixed bridge restorations (figures 3 and 3a).

When?

Because of this alveolar resorptive pattern after tooth extraction, bone grafting the extraction socket post-tooth extraction procedures has become a solution that attempts to limit the amount of hard- and soft-tissue loss. There are many systematic reviews in the literature that compare the results of residual ridge dimension following tooth extraction after the use of a bone graft (with or without a membrane) versus extraction alone without grafting. (7) Sockets that were preserved with bone grafting and/or membrane on average lost 2 mm less of ridge width, 1 mm less of ridge height, and had 20% more bone volume when compared to sockets that were not grafted. (8) Maxillary sites lost more than mandibular sites, and most ridge resorption occurred on the buccal aspect of the ridge.

Indications for bone grafting extraction sites include the following:

• Site development to increase hard and soft tissue for pontic sites in fixed bridge prosthetics (figures 4–4e)

• Rebuild defects around adjacent teeth after extracting teeth due to periodontal disease (figures 5a–5c)

• Correct bone defects impinging upon anatomical structures after tooth extraction, such as oroantral communication (figure 6)

• Preserve tissue structure for subsequent dental implant therapy

Decision matrix

With that in mind, does every extraction socket need to be grafted? The answer is no. A good decision matrix one can use is based on “A Simplified Socket Classification and Repair Technique” by Elian et al. (9)

Classification when existing tooth is still present:

• Type 1 socket—Buccal plate present and soft tissue present

Type 1a (figure 7)—Thick biotype, posterior tooth, and buccal plate present: no graft needed

Type 1b (figure 8)—Thick biotype, anterior tooth, and buccal plate present: clot stabilizer

Type 1c (figure 9)—Thin biotype, anterior or posterior, and buccal plate present: bone graft

• Type 2 socket (figures 10a and 10b)—Buccal plate missing, but soft tissue present: bone graft +/- membrane (if graft containment is needed)

• Type 3 socket (figure 11)—Buccal plate missing and soft tissue missing: bone graft + membrane +/- biologic agent (consider soft-tissue graft if keratinized tissue is less than 2 mm)

What?

Although there are many types of grafting products commercially available, choosing the right one may be difficult. An ideal bone graft substitute should be biomechanically stable; able to degrade within an appropriate time frame; exhibit osteoconductive, osteogenic, and osteoinductive properties; as well as provide a favorable environment for invading blood vessels and bone-forming cells. (10) The graft material used should facilitate the three tenants of bone regeneration: clot stability, space maintenance, and blood supply/bone-forming cells. (11) [Read more about bone grafts in “A review of bone graft material,” by Adam Bear, DDS.]

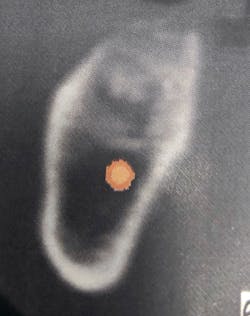

Unfortunately, many clinicians assume all grafting products are created equal and select the material based on price point alone. If the bone grafting material is not formulated correctly, degradation may not occur, and the graft can become fibrously encapsulated, leading to poor bone turnover and graft failure (figures 12a–12c).

One particularly good bone graft material that provides scaffolding space maintenance as well as stabilizes the blood clot is Geistlich Bio-Oss Collagen (Geistlich Pharmaceuticals). (12) Geistlich Bio-Oss Collagen is 90% Bio-Oss granules (size range 0.25–1.0 mm) and 10% collagen. The proprietary formulation of the collagen component gives the material its scaffolding and moldability qualities, which makes it an excellent product for site preservation after tooth extraction, especially during flapless site preservation. (13) Finally, this graft material has been shown to outperform other graft materials in comparative studies looking at site preservation after tooth extraction. (14)

Related video: Extraction and socket grafting in preparation for dental implant placement

This surgical video demonstrates removal of a tooth with loss of buccal plate and grafting of the remaining socket with Geistlich Bio-Oss Collagen and Geistlich Bio-Gide to preserve the ridge for implant placement.

Editor's note: Join us for the not-to-miss Perio-Implant Advisory Symposium on October 23, 2020. In this important virtual meeting, you’ll learn the newest skills it takes to save patients’ natural dentition. Bring your team and transform your practice. Conference schedule and special rates available at this link. Presented by Geistlich Biomaterials.

References

1. Dye BA, Thornton-Evans G, Li X, Iafolla TJ. Dental caries and tooth loss in adults in the United States, 2011–2012. NCHS data brief, No. 197. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db197.pdf.

2. Agarwal G, Thomas R, Mehta D. Postextraction maintenance of the alveolar ridge: rationale and review. Compend Cont Educ Dent. 2012;33(5):320-324; quiz 327, 336.

3. Hansson S, Halldin S. Alveolar ridge resorption after tooth extraction: A consequence of a fundamental principle of bone physiology. J Dent Biomech. 2012;3:1758736012456543. doi:10.1177/1758736012456543.

4. Schropp L, Wenzel A, Kostopoulos L, Karring T. Bone healing and soft tissue contour changes following single-tooth extraction: a clinical and radiographic 12-month prospective study. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2003;23(4):313-323.

5. Lekovic V, Camargo PM, Klokkevold PR, et al. Preservation of alveolar bone in extraction sockets using bioabsorbable membranes. J Periodontol. 1998;69(9):1044-1049. doi: 10.1902/jop.1998.69.9.1044.

6. Lam RV. Contour changes of the alveolar processes following extraction. J Prosthet Dent. 1960;10:25-32.

7. Avila-Ortiz G, Elangovan S, Kramer KW, Blanchette D, Dawson DV. Effect of alveolar ridge preservation after tooth extraction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent Res. 2014;93(10):950-958. doi:10.1177/0022034514541127.

8. Aimetti M, Manavella V, Corano L, Ercoli E, Bignardi C, Romano F. Three‐dimensional analysis of bone remodeling following ridge augmentation of compromised extraction sockets in periodontitis patients: a randomized controlled study. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2018;29(2):202-214. doi:10.1111/clr.13099. Epub November 17, 2017.

9. Elian N, Cho SC, Froum S, Smith RB, Tarnow DP. A simplified socket classification and repair technique. Pract Proced Aesthet Dent. 2007;(19)2:99-104; quiz 106.

10. Janicki P, Schmidmaier G. What should be the characteristics of the ideal bone graft substitute? Combining scaffolds with growth factors and/or stem cells. Injury. 2011;42(suppl 2):S77-S81.

11. Mellonig JT, Triplett RG. Guided tissue regeneration and endosseous dental implants. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1993;13(2):108-119.

12. Araújo Mauricio, Linder E, Wennström J, Lindhe J. The influence of Bio-Oss Collagen on healing of an extraction socket: an experimental study in the dog. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2008;28(2):123-135.

13. Cardaropoli D, Tamagnone L, Roffredo A, De Maria A, Gaveglio L. Alveolar ridge preservation using tridimensional collagen matrix and deproteinized bovine bone mineral in the esthetic area: a CBCT and histologic human pilot study. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2018;38(suppl):S29-S35. doi:10.11607/prd.3702.

14. Scheyer ET, Heard R, Janakievski J, et al. A randomized, controlled, multicentre clinical trial of post‐extraction alveolar ridge preservation. J Clin Periodontol. 2016;43(12):1188-1199. doi:10.1111/jcpe.12623.

Editor’s note:This article originally appeared in Perio-Implant Advisory, a chairside resource for dentists and dental hygienists for issues relating to periodontal and implant medicine. Exclusive content from an academic perspective centers on complex care, solving clinical complications from a team-based approach through interdisciplinary management.